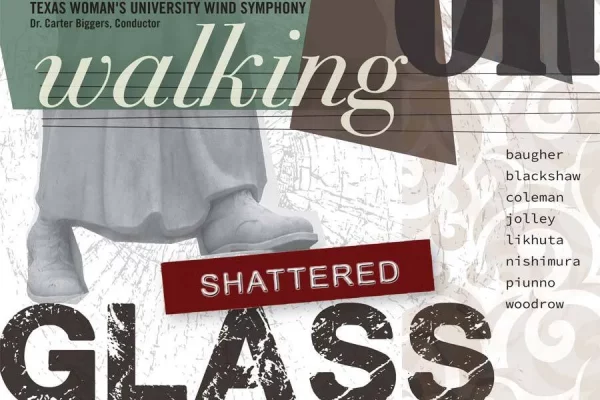

A “hell” or “slick” or “wooly-head” or “yaller patch” is a thicket of laurel or rhododendron, impassable save where the bears have bored out trails.

-Horace Kephart, Our Southern Highlanders

Japanese American singer-songwriter Mitski seems to be at an impasse with her music career; she seems to simultaneously both love and abhor the career she’s found impossible to let go, returning shortly after announcing in 2019 that she was to quit music completely, and it shows in her latest, full-length album, “Laurel Hell.”

An artist in little need of introduction this deep into the 21st century, New York-based, sad-girl musician Mitski Miyawaki, stage name Mitski, is back with her sixth studio album, a decade after her debut album “Lush.” Going from indie darling to hit-making, pop force in the industry, she has garnered both critical and public acclaim for several of her albums, such as “Bury Me at Makeout Creek” and “Puberty 2,” and is known best for her unflinching, confessional lyrics accompanied by sometimes raw, often-times beautiful arrangements that have infested the minds of a population seeking relatable music that veers from the saturated, Top 100 landscape.

As she continues to rise in popularity, however, things have begun to unravel for the artist that once released unrivaled pieces of modern music, a horrific notion that was foreshadowed by her last record’s, “Be the Cowboy’s,” uneven track list has unfortunately reared as a bland manifesto of artistic ennui in this latest collection of tracks. In an interview with The Guardian’s Ben Beaumont-Thomas, Mitski, speaking on the difficulty of artistic vulnerability when accompanied by the relentless zeal of her fanbase, says “it almost doesn’t matter what music I write and put out into the world. At the end of the day, I’m a woman in public, allowing myself to be consumed,” a sentiment that runs deep through the roots of the album and whose original thematic manifestation runs wild within the new LP, co-existing with the usual affair of sexual desire and heartbreak.

The record begins with its best set of tracks, opening with “Valentine, Texas.” The track sets the tone for the album perfectly, heavy, ominous notes leading into Mitski’s competent lyricism that evokes feelings of self-doubt and longing, using the listener as a surrogate for her words as she briefly promises that this record will be unprecedented in its honesty in the first verse, before an explosion of synths breaks on through the middle of the track. Leading into the second verse, she conjures the imagery of a supernatural desert lying on the outskirts of a dying Texas town in the 1950s where people grow and die without stepping a foot into a world, a town that Mitski and her lover are making smaller and smaller in the presence of the rearview window, enough distance for her to be comfortable enough to admit her longing for the weight of the world to be off her shoulders, a picturesque soundscape that then leads to the first single of the record, “Working for the Knife.”

Admittedly, the track fell flat on initial release, but the track was simply missing the context of the surrounding record to complement its lyrics and music, relying heavily on a startling degree of cynicism and lost naivete to expound on the tragedies that come with working under an oppressive force, whether that be the music industry, her audience, or personal struggles. “Working for the Knife” is a ballad that, in hindsight, is an appropriate manifesto for her return from a two-year hiatus.

Signing off the trilogy of decent music comes the highlight of the record, “Stay Soft,” a thoroughly enjoyable voyage of twisted sexuality that screams “classic Mitski,” a recounting of a volatile relationship soaked in all manners of toxicity, the most observed being the use of sexual intercourse to make the pain make sense, all espoused over a comparatively innocuous dance beat complemented by dark piano. Even then, the track can only reach levels of Mitski “lite,” missing a certain level of rawness and power that, in its absence, leaves the track feeling slightly hollow.

Sadly, the record begins to falter from here on out, reaching another peak on the second half with the track “Should’ve Been Me,” a decent track with lyrics that fit well in her oeuvre that suffers most with its instrumental. More specifically, there is a certain bell sound that hits way too often every few seconds, sounding like a ringtone in the worst way that puts a handicap on the song’s enjoyability.

Not all the middling tracks in this record were made equal, songs like “Everyone” and “I Guess,” both serve as a double entendre for Mitski’s feelings on both floundering relationships with loved ones and the constricting nature of her relationship with her fans, brought down mostly by a meandering and flat sound, respectively. “Love Me More” has the best sound of the singles and a compelling theme of self-isolation as a means of removing the chance of heartbreak, but the chorus is the most under-written in the entire album; even though her attempt to translate a sense of desperation via repetition is visible, it doesn’t make the chorus any less of a drag. The verses also slightly suffer similar symptoms, but only to a lesser extent.

The worst offender in the track list is “There’s Nothing Left for You,” a horrendously boring and under-written track whose skeletal approach in its poetry proves to be detrimental rather than evocative, making it a flat track that is an amalgamation of everything gone wrong for what Mitski was attempting. One of the other more baffling tracks, “Heat Lightning,” begins with a sound that makes me want to turn it off and listen to the Velvet Underground’s “Venus in Furs,” as it is so reminiscent to be bordering on mimicry. There really is no winning on this track, as once it loses the Velvet Underground influence, it is stripped into the most boring track in the record.

“The Only Heartbreaker,” even with a co-writer, is a track Mitski could not completely make the landing on, as it has the weakest grasp on its identity out of the entire tracklist, with a set of lyrics that detail this almost unsympathetic portrayal of a character desperate for her lover to make a mistake so she isn’t the only bad guy. The narrative is made tolerable by the bridge’s set of lyrics, repeating “I apologize/You forgive me,” hinting that there is more at play under the surface, but as is, the lyrics suffer from their own confusing narrative. If the lyrics are ignored though, the 80s sound makes for decent background Muzak, suitable for a drive with friends, all that to say, it does not hold up on its own as a listening experience and is best used as a supplement to other events.

The finisher, “That’s Our Lamp,” is a depressingly unfitting track to end the record on, a huge miss in terms of placement in the track list leaving the listener with no strong impressions; the effect on the guitar is unflattering and the contents of the track can be summed up as a boring break-up song that only slightly sounds like a light goodbye, doing nothing to build on the themes of the album, something that is done better by a track as out of kilter as “I Guess.” Though the sound is about as attention-grabbing as the flat title, the lyrics and sentiment of the song elevate the song with a sense of purpose and potentially even finality, for it is a tale that can be seen as a continuation of the romantic breakup themes where she is left to put the pieces back together, it can also be seen as a somber epitaph to her relationship with the music she has made, a much more fitting ending.

In attempting to capture both the emotions of her classic, damaged-relationship songwriting and the new themes of an artist’s imprisonment to her image, her para-social audience and the music industry, she captures none, leaving only a series of half-hearted musings, languidly executed by what feels like a xerox of the darkly emotional maestro.

The name of the disappointing record, “Laurel Hell,” is the best decision Mitski has made regarding the creation and cultivation of her latest album; the record works on multiple levels: on the surface, the music is a representation of her current feelings in regard to thrusting herself back into the limelight to uncomfortably expose all her vulnerabilities to her antsy legion of fans, as it is this exhibition of atrocity that keeps her afloat.

On a metatextual level, the realm where readers and listeners alike inhabit, the album is a figurative “yaller patch,” an inescapable thicket of self-indulgent drudgery with glimpses of thematic and musical cohesion, the metaphorical “bear trails” that hint at an escape, that eventually must relapse into an indiscernible wall of numbingly-uniform, ‘80s pastiche that’ll leave you yearning for the soundwaves of a “Makeout Creek.” Deep down there is an underlying knowledge that the failure here is not a product of incompetence, but one of inadequate soul, and that is the real heartbreaker.

Jesus Reynaldo Valdes can be reached via email at jherreravaldes@twu.edu.

Be First to Comment