Warning: This article discusses topics regarding violence and death.

In “Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story,” the story of one of the world’s most infamous serial killers is once again told, representing his pursuits of his 17 known victims, his arrest and eventual prosecution.

This is not the first time Dahmer’s representation has graced the big screen. “My Friend Dahmer,” another fictional recreation, was produced about the years leading up to Dahmer’s killing spree in 1978. The film garnered criticism with accusations that the film was glamorizing Dahmer and his crimes.

Since debuting on Sept. 23, the show has received criticisms almost as quickly as its gained popularity. The show has delivered engaging storylines and excellent acting, especially by the show’s star, Evan Peters, but this may actually prove to be the show’s downfall.

On Sept. 25, Rita Isbell, the sister to victim Errol Lindsay, wrote a personal essay in which she described her reactions to the show. In this essay, she describes that she was never contacted about the show, despite having a portrayal of her delivering an emotional victim impact statement. She wrote, “I’m not money hungry, and that’s what this show is about, Netflix trying to get paid.”

The fascination with forensics and criminology is not found in the fictional recreation of a tragedy.

At the root of the true crime movement that has swept the nation is the new market fueled by capitalism that tries to make a quick buck off of another’s suffering. Anne Schwartz, the reporter who broke the Dahmer case, has gone on to point out that the show sacrificed accuracy for the sake of drama. It does not matter if you portray him as a damaged soul or a psychopath; it is still adding to the legend. By dramatizing and fictionalizing this show, the mythos of Jeffery Dahmer, the all-American serial killer is continued.

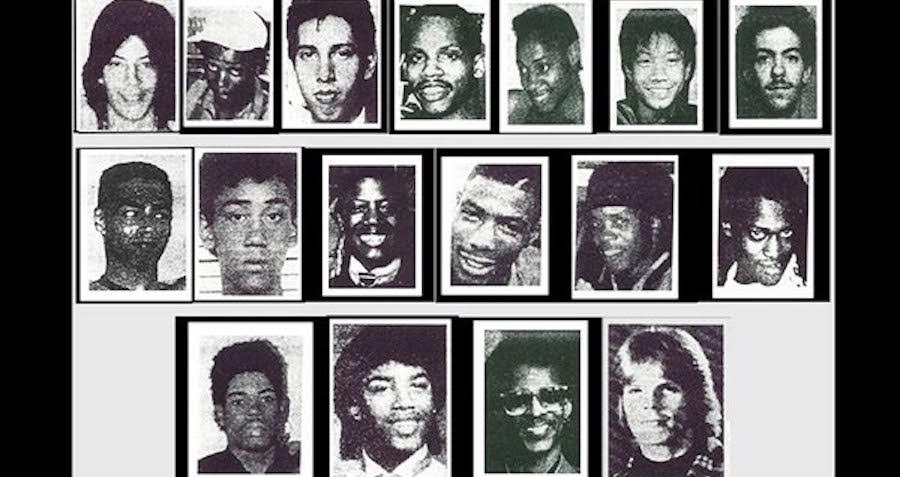

With a fictional recreation of a true event, producers fill in the blanks with the most tantalizing mad-libs they can muster up in order to increase engagement, or they draw these conclusions from the most unreliable of narrators: the killers themselves. In promotional materials for this series, the producers expressed that they aimed to tell the victims’ stories and not provide solely Dahmer’s point of view, but the series spends little time with anyone other than Dahmer. The lives of his victims are relegated to their relation to Dahmer, rather than as independent individuals lost far too soon and known almost exclusively as a summary of last known sightings, ages and races.

Dahmer targeted those known as the “less-dead,” a term criminologist Steven Egger has used to describe marginalized groups that are seen as less likely to have the same response from police and the public as a white, straight person would. Dahmer, like many prolific serial killers, targeted those he thought would not be reported missing.

His victims were majority LGBT+ people of color that did not receive the same protection under the law as their white, straight counterparts. Dahmer would often speak at lengths in bars and on the streets in order to gain the trust of and prey on men who were on the margins of society.

Jamie Doxtator and Konerak Sinthasomphone were 14 years old, barely teenagers when their lives were taken. Anthony Sears was going to celebrate his recent promotion over Easter dinner with his family. Steven Hicks had just graduated high school and was hitchhiking to a rock concert.

With all of these lives, they never made it to their concert or family dinner.

The introduction and popularity of this show have broadened the conversation around the ethics of the true crime genre. The criticisms of the show have helped to promote the sentiment that Eric Perry, a relative of Errol Lindsey, said, “we are all one traumatic event away from the worst day of our lives being reduced to our neighbor’s favorite binge show.”

Maddie LaRosa Ray can be reached via email at mray10@twu.edu.

Be First to Comment